Table of contents

Introduction

In the SOCS exercise sessions, you will learn how computers execute programs. We will explain high-level concepts in the C programming language, then show how these concepts are translated to assembly code by the compiler. You will also learn how the CPU executes the (generated) machine code, and which hardware features are used to make this code more performant.

The following table shows which layers of the hardware-software stack of computers is covered by SOCS and by other courses. SOCS covers a broader range in this stack than many other courses.

| Course | Topics | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Objectgericht programmeren | Object-Oriented Code | Car c = new Car(); |

| SOCS | Procedural Code | malloc(sizeof(...)); |

| SOCS | Assembly | add t0, t1, t2 |

| SOCS | Machine Code | ...0100110111010... |

| Digitale Elektronica en Processoren | Digital Hardware | Logic gates |

The majority of the sessions will focus on writing assembly programs from scratch. The first two sessions are more theoretical and might be a bit overwhelming, but understanding the concepts covered now will be very important for the later sessions. You can also come back here to refresh your knowledge when these concepts come up in later sessions.

If you have any questions or anything is unclear, ask your teaching assistant or reach out to us on the Toledo forums!

Architecture basics

Modern computers are made up of several hardware components. Most of these computers follow the so-called von Neummann architecture. This means that the random access memory (RAM) contains both program code and the data this program calculates on. (This is in contrast to Harvard architectures, where the instructions and data are stored in separate memory modules.)

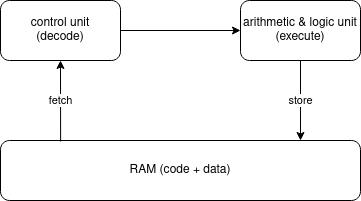

The computer’s operation is sometimes called the fetch, decode, execute cycle. Instructions are fetched from RAM, decoded by the control unit, then executed in the arithmetic and logic unit (ALU). Finally, the result of the computation might be written back to RAM.

These designs are called stored-program computers, highlighting that the code that is executed is stored in memory. These instructions are stored in machine code format (see later), which is often directly compiled from a high-level program by a compiler.

The computations are usually performed on values stored in registers. Registers allow values to be stored inside the CPU (but there are only a few of them). Accessing registers is much quicker than accessing the RAM, so registers enable faster computations than if the values were fetched directly from RAM. In fact, in later sessions we will see how caches are used to speed up accesses to values that are not stored in registers and have to be fetched from RAM. The following diagram shows this memory hierarchy; access times increase dramatically when moving towards the right.

Machine code refers to the binary format of instructions that the CPU can execute. These are usually simple instructions, such as adding or subtracting register values, or loading and storing memory values. The (human readable) assembly language representation of these instructions is called the mnemonic form. An assembler program can compile the mnemonic programs into machine code. You will see this in the RARS environment.

- Machine code:

00000000010100000000001010010011 - Mnemonic form:

addi t0, zero, 5

The C programming language

In SOCS, we will use the C programming language to showcase programming concepts which we then translate to RISC-V assembly. We chose this language because it’s widely used in systems programming, its procedural style is not so different from assembly as some other languages (such as object-oriented languages), and it’s easy to examine the compiled assembly code using built-in tools of the operating system.

C and other languages

Many features in modern programming languages were inspired by C, so you will find plenty of similarities with modern languages when writing C, hopefully making the transition easier. Some of these include how you declare and use variables, writing loops and conditional statements, or working with functions.

In other aspects, C has a closer connection to the underlying operating system concepts. The programmer needs to manage dynamic memory manually; for variable length objects (such as lists containing an arbitrary number of elements) the programmer has to manually request memory chunks from the operating system and return them once they are no longer needed. Many features in C also require explicitly working with the memory address of certain variables, not only their values.

The very basics of C

Before considering on how to even run a C program, let’s look at the basics. C is a statically typed language, this means that the type associated with each and every variable must be known before compiling.

Here are some of the most common types in C:

| Type | C notation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| signed integer | int | 1, 2, -5, 6… |

| unsigned integer (non-negative values) | unsigned int | 1, 2, 3, 4… |

| signed integer, at least 32 bits | long | 1, 2, -5, 6… |

| character | char | “a”, “b”, “z”… |

| floating point number | float / double | 1.5, -2.354, 0.001… |

| void | void | no type, no value |

For floating point numbers, you can use float and double (where the latter has double the precision).

Characters can be stored in the char type. This is 1 byte in size, so it stores the character in the ASCII encoding.

In your C programs, you can find the precise size of a data type or a variable (in bytes) with the sizeof() function: sizeof(int) or sizeof(a).

A very simple example, containing only variables:

int x; // Declaration of the variable x

x = 5; // Assignment of the variable x

int y = 10; // Both at once

If we want to do something with these variables, we could insert a function. Don’t worry if you do not understand this part yet, in the fourth exercise session we will go into more depth on functions.

Let’s look at a very simple program that adds two numbers together:

int add(int a, int b){ // We make a function called add, which takes two arguments: a and b which are both an integer

return a+b; // The function add returns an integer

}

int main(void){ // The main function takes nothing as an argument, hence the 'void'

int x;

x = 5;

int y = 10;

int result = add(x, y); // We call the function add

return 0; // We return 0 here since our main function is of the integer type (More on this later)

}

Notice the int main(void){} function, this is mandatory in every single C program.

What if you wanted to put the code of the int add(int a, int b){} function below the main function? Since the compiler reads the source code file from top to bottom, it will panic if it sees the function call to the add function inside int main(void). Since it doesn’t recognize it. This is where a function declaration comes into play, see the code segment below. This declaration simply stands for: I know this function is missing, but trust me, it exists somewhere later.

Now consider the following equivalent program:

int add(int, int); // This is a function declaration

int main(void){

int x;

x = 5;

int y = 10;

int result = add(x, y);

return 0;

}

int add(int a, int b){

return a+b;

}

If you try to run this program for yourself, you will hopefully notice there is no output being printed. We will see output in Dissecting hello world.

Compiling C

Let’s test your C compiler setup with a simple hello world example.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

printf("Hello world!\n");

return 0;

}

If you save this program into a file hello.c, you can compile and run your program with the following commands:

$ gcc hello.c -o hello

$ ./hello

Hello world!

The gcc invocation on the first line creates an executable file hello, which we can then run with ./hello.

Warm-up: Make sure that this works on your computer!

If you’re curious, you can also ask the compiler with the -S flag to create a human-readable assembly file from your program (instead of the executable hello containing machine code). Don’t worry if you don’t exactly understand what you’re seeing!

$ gcc hello.c -S

$ cat hello.s

.file "hello.c"

.text

.section .rodata

.LC0:

.string "Hello world!"

.text

.globl main

.type main, @function

main:

.LFB0:

.cfi_startproc

endbr64

pushq %rbp

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 16

.cfi_offset 6, -16

movq %rsp, %rbp

If you’re working on your computer, there is a good chance that you’re compiling for the x86 architecture, so the output you see here is x86 assembly code (not RISC-V).

You can use the website Godbolt to see the assembly output of different compilers, targeting different architectures. As an example, you can select the compiler RISC-V rv32gc gcc 10.2.0 on the site to see RISC-V assembly code as your output. This is a handy tool for quick experiments, but of course for larger projects you should stick with a local compiler setup.

Warm-up: Check the RISC-V assembly code on Godbolt for the

hello worldprogram!

Dissecting hello world

Let’s go back to the example code:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

printf("Hello world!\n");

return 0;

}

The first line tells the compiler to include parts of the C standard library, this enables us to use predefined functions, such as the printf we use to print to the console. This #include directive is similar to import in Python or Java. In this case, we include the stdio.h header, which includes functions related to input/output (standard input/output).

We use the printf function from stdio.h to print the text “Hello world” followed by a line break (\n). Later in this session, we will see how to print values of variables as part of our string.

C programs always have to contain a main function. This is where the execution will start from when we run our program. The signature int main(void) tells us that the main function returns an integer value and does not take any parameters (void). The return value of the main function usually signals whether the execution was successful. 0 means success, while other values may be interpreted as error codes.

Integers in C

You can use integer variables and basic arithmetic operations in C like in many other languages.

int a = 4;

int b = 5;

int c = (a + 3) * b;

Every variable (a, b, c) in C is stored at a given memory location. By performing operations on these variables (such as addition or multiplication), we basically perform these operations at the values stored at the corresponding memory locations.

A look forward: You can access the memory address of a variable by adding

&in front of the variable name. For example, in the program above,arefers to the value4, but&arefers to the memory address where that4value is actually stored.

Handling user input in C

Programs that do not deal with any inputs and do not print any results are pretty useless. We have already seen how to use printf to write a string literal to the console. It’s also possible to print out the values of variables using printf. In the other direction, we can use the function scanf to read user input into variables.

printf and scanf are functions that can take an arbitrary number of arguments. The first argument of these functions is called the format string. This specifies the format (the “shape”) of the string we want to print out or read in. We can include format specifiers in this string, these are placeholders for the variables we want to include in the string.

If for example we want to print out the value of an int age variable as part of our string, we would include the %d (decimal) format specifier in the format string as a placeholder for the value of the variable: "I am %d years old.".

For different types of variables, we need to use different format specifiers; %c for characters, %u for unsigned integers, etc. After the format string, we include the variables as arguments to the printf functions in the order of the format specifiers.

int age = 21;

int ects = 36;

printf("I am %d years old and I have %d ECTS this semester. Phew!\n", age, ects);

With scanf, there are two things you need to watch out for. First, you need to pass the memory location where you want the input to be written. In practice, this often means taking the memory address of a given variable:

int input;

printf("Enter your favorite number: ");

scanf("%d", &input);

Second, notice how we printed the prompt to the user using printf, not as part of the scanf format string. Remember, the scanf format string describes the shape of the string the user has to enter! In this case, we want the user to simply enter 5, or another decimal number, so the format specifier %d is all we have in the format string.

If we want the user to enter their favorite time in the day, we could have a prompt like scanf("%d:%d", &hour, &minute);. In this case, if the user enters a string like 13:37, the number 13 will be saved to the hour variable, 37 will be saved to minute, and the : in the middle will be ignored.

In general, if the user’s input does not respect the format specified in scanf, strange values can appear in your program.

Most commonly found format specifiers:

| Format specifier | Usage |

|---|---|

| %d | For decimal values, so usually signed integers |

| %p | For pointers, so memory addresses |

| %u | For unsigned integers |

| %s | For strings |

| %c | For a single character |

| %lu | l stands for long, u for unsigned int -> Long unsigned integers |

More exhaustive list with examples

Exercise 1

Write a C program that asks the user for an integer value and prints out the square of this value, together with the original number.

Solution

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

int n;

printf("Your number: ");

scanf("%d", &n);

int square = n * n;

printf("The square of %d is %d\n", n, square);

return 0;

}

Pointers in C

As mentioned before, variables in C are stored in memory locations. To perform operations on these values, first they need to be loaded into registers (usually using the lw instruction in assembly).

You can use the & operator to get the memory address of a given variable. Notice that we have already used this syntax in scanf, where we needed to specify where in memory the user input should be written. Later, we will see other examples where the memory addresses play an important role in how C works.

Given the importance of addresses, C allows us to store them in special variables called pointers (pointing to a memory location). These variables have an asterisk in their type to indicate that they are pointing towards a value with that given type:

int a = 5; // a regular integer, stored somewhere in memory, `a` stores the value 5

int *p = &a; // a pointer to an integer value, `p` stores the memory location of `a`

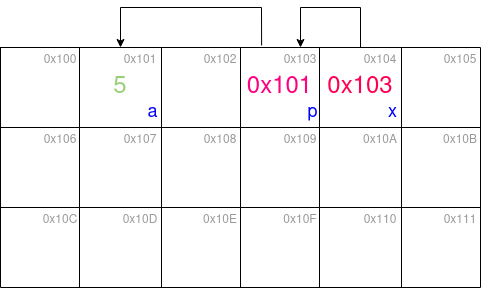

We can visualize the memory layout the following way (ignore x for now):

In the picture, each cell represents a location in memory, the addresses of these locations are displayed in gray in the top right corner. When we create a variable in C (identifier in blue, bottom right), it will get assigned to one of these locations. The contents of the memory location are displayed in the middle.

Integer values are displayed in green, while pointers are in shades of red. Pointing to a memory location (visualized as an arrow) simply means storing the address of that cell.

We can print out the value of a pointer using the %p format specifier:

printf("The address of `a`: %p, its value: %d\n", p, *p);

// The address of `a`: 0x0101, its value: 5

Notice how we got the value of the pointed memory location by using *p. So while writing p gives us the address of a, writing *p gives us the value at the pointed address. Writing the asterisk is the equivalent of following an arrow in the picture above to arrive at the pointed value. We can also use this to change the value at that address:

int a = 5;

int *p = &a;

*p = 6;

printf("a = %d\n", a);

// a = 6

Pointers will allow us to change the values of variables that we do not have direct access to. We will see examples of this later.

As you can see, p is also a variable, it also has an address: p needs to store its value (the address of a) somewhere in memory, so it necessarily has its own address, which you can get with &p.

So what type of variable do you need to use if you want to store the address of p (in variable x in the example above)?

Solution

int **x = &p; If you see a variable with a pointer type, and you want to find out what type of value it points to, a handy trick is to cover the asterisk closest to the name. This will give you the type of the variable the pointer points to. For example, with int *p = &a;, by covering the asterisk, we see that it points to an integer variable (a). With int **x = &p;, when we cover the last asterisk, we still have int * remaining, so we know x points to an integer pointer (p)!

Exercise 2

Write a C program that asks the user for an integer. Print the address, the value and the size in bytes of this integer. Now store the address of this integer in a pointer. Then print the address, the value and the size in bytes of this pointer.

In the picture demonstrating pointers, we have made some simplifications regarding the sizes of variables. Can you see what wasn’t realistic in that example?

Solution

In the picture, integers and pointers are stored as a single byte (the memory cells have addresses that increase by 1), whereas according to the standard they should be at least 2 bytes long. This program will tell you exactly how many bytes these types use on your computer.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

int num;

printf("Your number: ");

scanf("%d", &num);

printf("Address: %p, value: %d, size: %lu\n", &num, num, sizeof(num));

int *pointer = #

printf("Address: %p, value: %p, size: %lu\n", &pointer, pointer, sizeof(pointer));

return 0;

}

Exercise 3

Write a C program that asks the user for a positive integer and iteratively computes the factorial of this integer.

Hint: loops work the same way in C as they do in many other languages. Basic structure:

while (condition){}

Solution

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

int n;

int fac = 1;

printf("Your number: ");

scanf("%d", &n);

while (n > 0) {

fac *= n;

n--;

}

printf("The factorial is %d\n", fac);

return 0;

}

Additional exercises

Exercise 4

Create a function swap(int *a, int *b) that takes two pointers and swaps their values. Implement the swap function below the main function, but ensure you can call it from inside the main function. Test your function by printing the resulting integers.

Solution

#include <stdio.h>

void swap(int *a, int *b);

int main(void) {

int a = 1;

int b = 2;

swap(&a, &b);

printf("a: %d\nb: %d\n", a, b);

return 0;

}

void swap(int *a, int *b) {

int temp = *a;

*a = *b;

*b = temp;

}

Exercise 5

In C a user can supply data to a program using arguments. These arguments are received in the main function using the argc (argument count) and argv (argument vector) parameters. argc represents the amount of arguments given to the program. argv is an array (think of a list) of arguments given to the program. The first element is always the program name.

You’ll see arrays in session 3, but you don’t need to know everything about them to solve this exercise. For now, think of an array as a pointer pointing to its first element. A string is a character array, represented as a char *. argv is an array of such pointers.

Knowing this, try to figure out the type of argv and print out the first argument (argv[0]). You should see the name of the program.

Solution

The type of argv would be char **argv (or char *argv[]).

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc > 0) {

printf("The first argument is: %s\n", argv[0]);

}

return 0;

}