Table of contents

Cache simulator

Number of sets:

Number of ways:

Block size (words):

Insert element (address):

Introduction

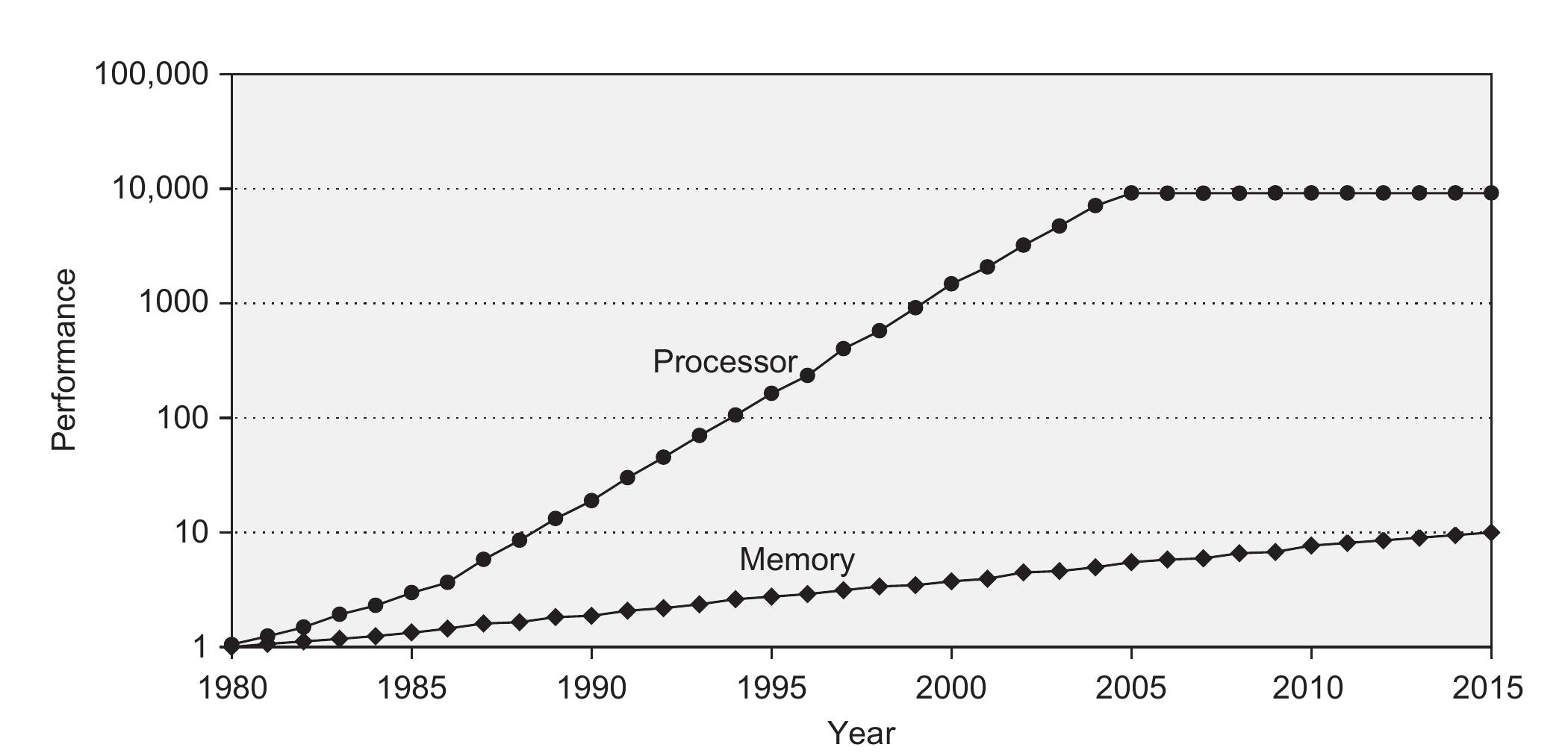

Over the years, a performance gap has formed between the processor and the memory unit. As shown in the figure below, processor performance has been increasing much faster than memory performance. Consequently, the processor has become much faster than the memory, forming a bottleneck for the performance of the computer in general.

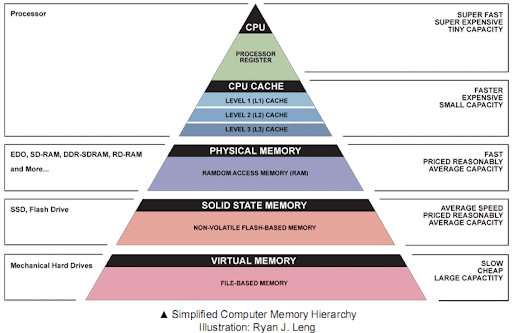

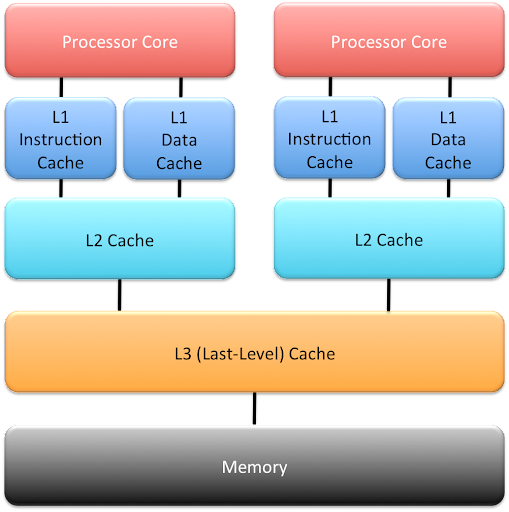

To solve this issue, caches were introduced. Cache memories are not as fast as registers, but can include more data, and are much faster than the main memory. However, they are also more expensive than the main memory and therefore a lot smaller. Most commercial CPUs typically offer a hierarchy of caches: Level 1 cache (L1) is the fastest but also the smallest cache, Level 2 cache (L2) is slower but larger, and the last level cache (L3 or LLC), which is the slowest but the biggest.

Caches can be local to a single processor core (this is typically the case for L1 and L2 caches), or shared across multiple cores. Finally, the L1 cache is usually split into an instruction cache (L1I), which contains program instructions, and a data cache (L1D), which contains program data.

Locality principle

Programs usually access a relatively small portion of the address space at a time.

In particular, when a program accesses a given memory location (a variable), it is likely to access that same location again in the near future. This is called temporal locality. Hence, a memory location that is accessed by a program can be cached to speed up future accesses!

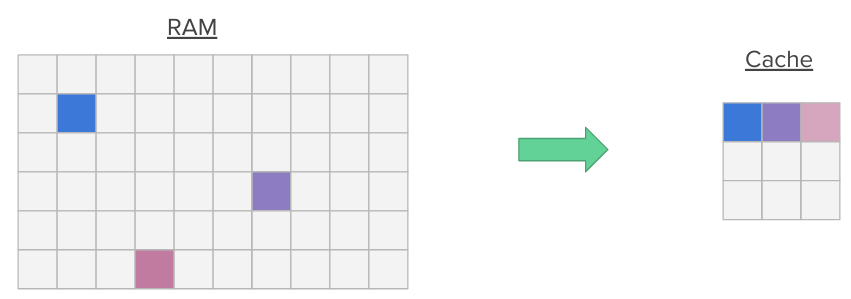

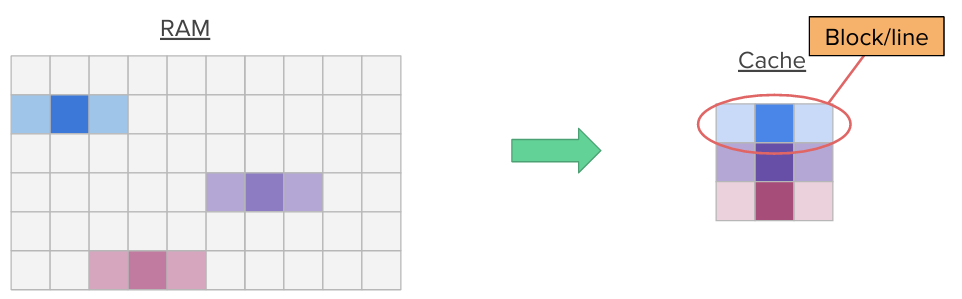

Additionally, when a program accesses a memory location, it is likely to access nearby memory locations in the near future (think for instance about nearby variables on the stack or nearby array members). This is called spatial locality. Hence, when a memory location is accessed, we transfer entire blocks (multiple contiguous words in memory) into the cache at once, pulling nearby data into the cache.

By exploiting these two locality principles, caches can cause a huge performance gain, even though they are small.

Terminology

Consider a program that accesses a memory address: lw t0, 0x10010000.

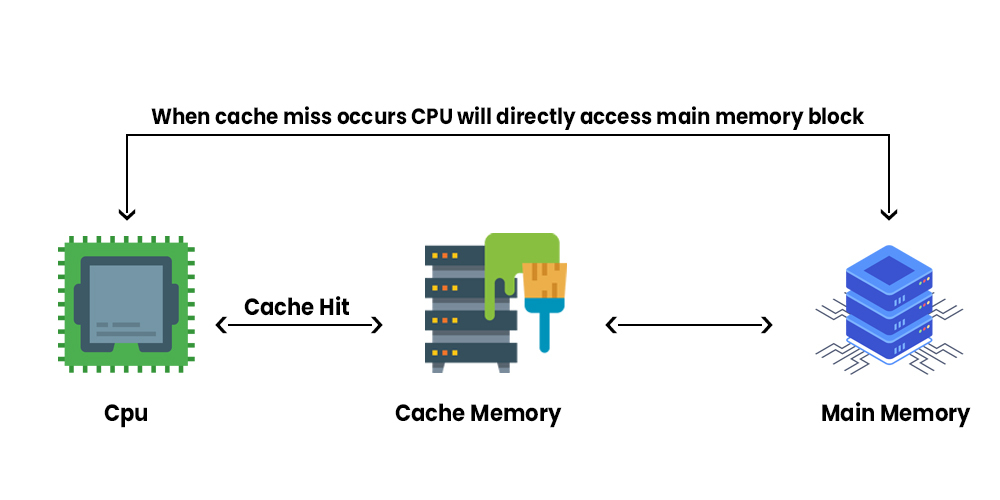

We say that we have a cache miss if the address 0x10010000 is not in the cache (for instance if it is the first time it is accessed by the program). In that case, the value is requested from the DRAM and the memory access is slow. The value is then placed in the cache for later use (following the temporal locality principle).

We say that we have a cache hit if the address 0x10010000 is in the cache. In this case, the corresponding value is directly served from the cache and the memory access is fast.

We can express the performance of the caching algorithm with the hit rate, which is the number of cache hits divided by the total number of memory accesses. We can also talk about the miss rate, which is equal to (1 - hit rate), or (cache misses / total accesses).

Cache placement policies

The cache placement policy determines where a memory address should be placed in the cache.

Direct mapping

Let us start with the structure of the cache. In our examples, we consider byte-addressable memory, meaning that data is stored and accessed byte-per-byte (contrary to a word-addressable memory where data is stored word-per-word). The cache is a table that contains multiple rows, these are called the cache sets. A cache set can include one or more cache blocks (a block is sometimes also called a cache line, which can be slightly confusing in our representation, since a cache set is represented as a row [or line] in the cache table, which can contain multiple cache lines).

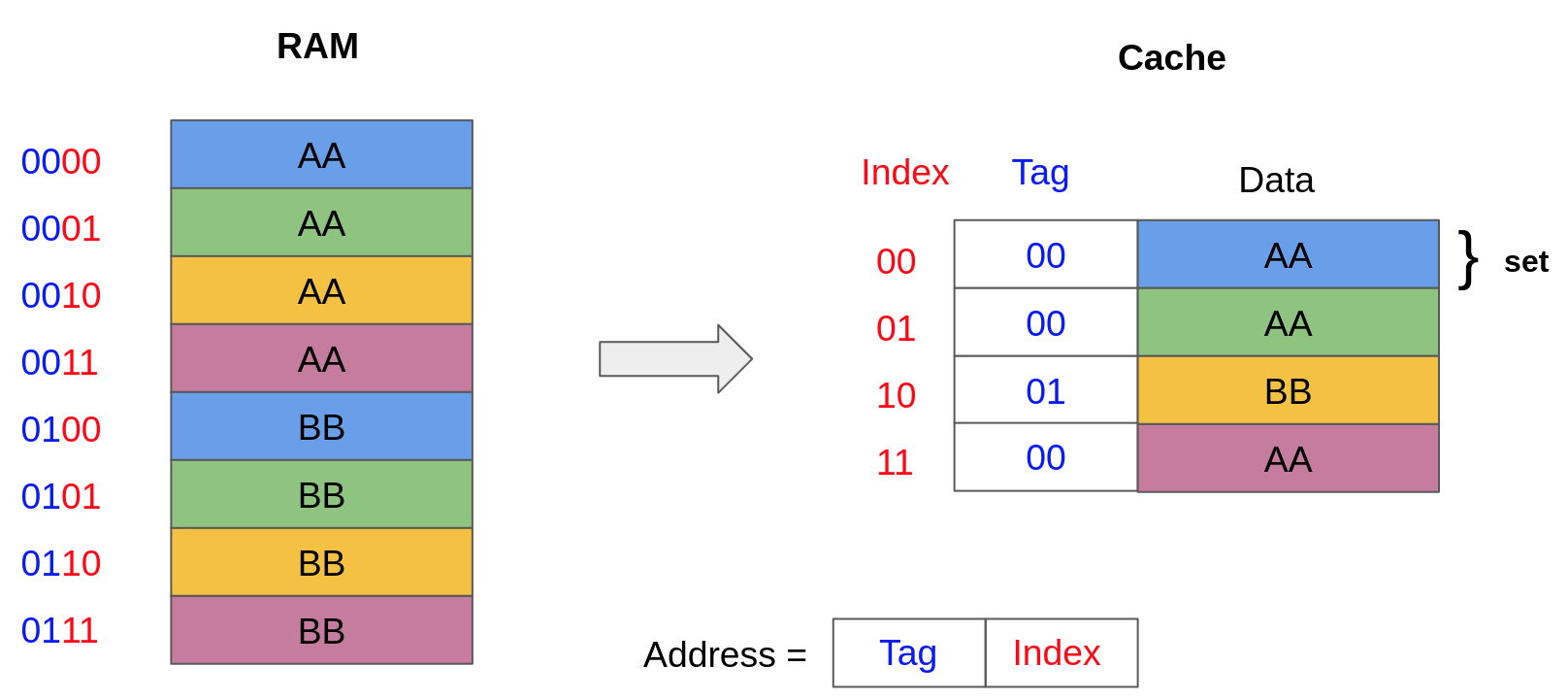

The simplest cache placement policy, called direct mapping, maps every memory address to a unique block in the cache.

Take for instance the cache model given below, where each cache set only contains a single block. Given a memory address, the index of the corresponding cache set is determined using the two least significant bits of the address (index = address % 4). Because multiple addresses map to a single cache block, the cache also needs to keep track of a tag, corresponding to the most significant bits of the address. Therefore, given an address, the index determines where to look for the data in the cache and the tag indicates whether we have a cache hit or a cache miss.

A memory address, composed of a tag t and an index i, is in the cache (cache hit) if the tag at index i in the cache matches t. For instance, accessing the address 0001 (i.e. tag=00, index=01) results in a cache hit because the tag in the cache at index 01 is 00. However, accessing the address 0010 (i.e. tag=00, index=10) results in a cache miss because the tag in the cache at index 10 is 01.

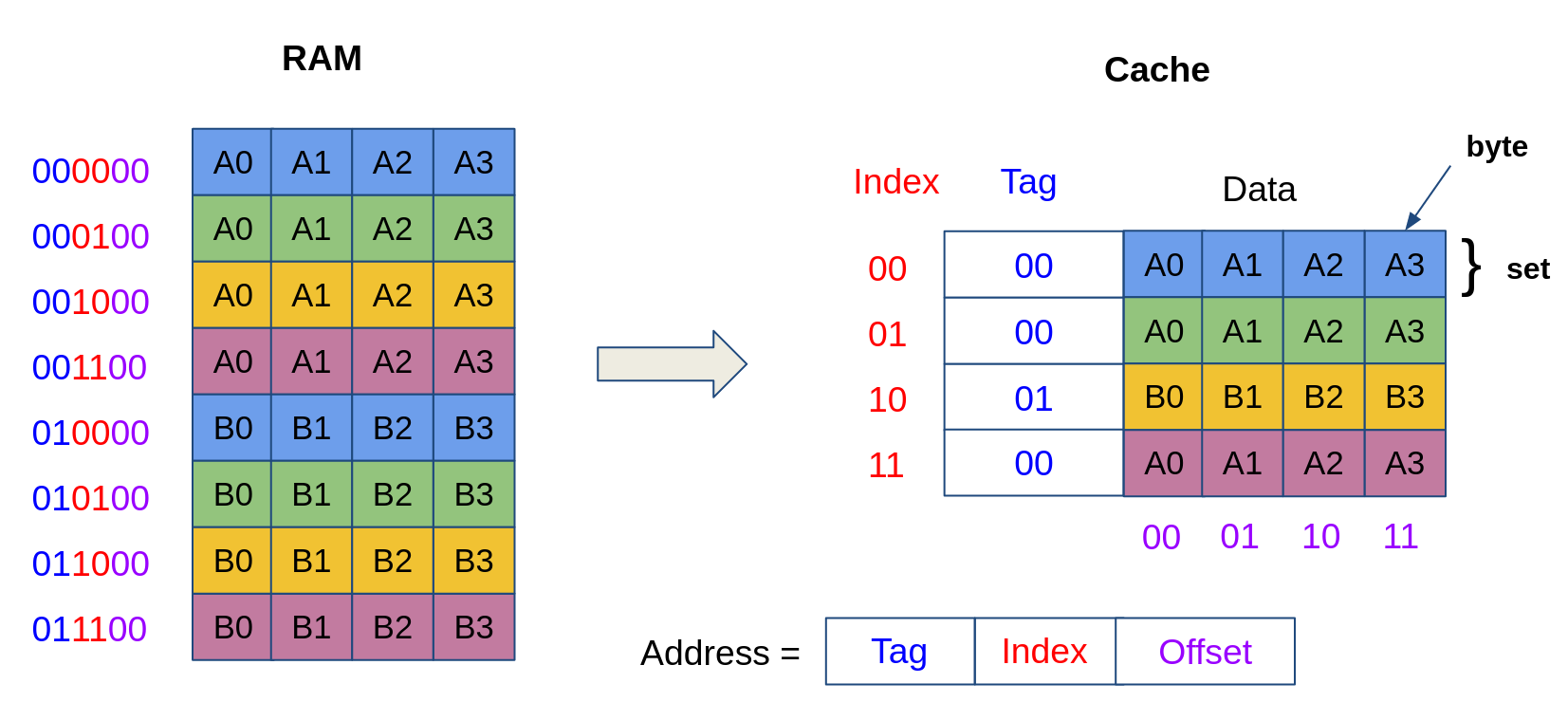

The data in one cache block typically contains more than one byte. This is to enable spatial locality; when the data from a certain address is loaded, the contents of the neighboring memory locations are also placed in the cache, in case they are also accessed in the near future.

For instance, in the cache model given below, the size of a block is 4 bytes. The lower bits of the address correspond to the offset of the data in a cache block. For instance, the address 001000 corresponds to the value A0, while the address 001001 corresponds to the value A1.

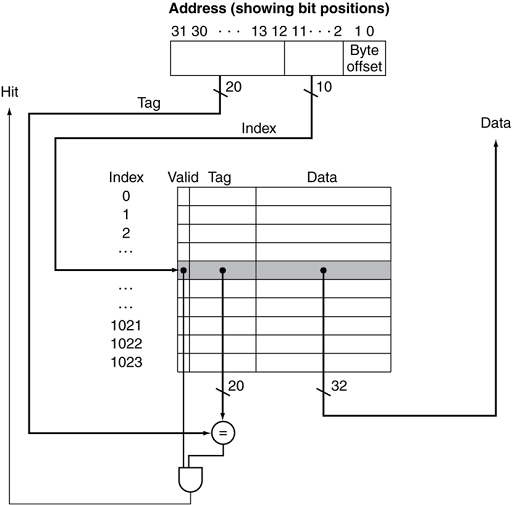

Summary

A memory address (of size 32 bits) is composed of:

- an offset (the least significant bits of b) which determines the offset into one cache block;

- an index (the next k bits), which determines the cache set;

- a tag (the remaining 32-(k+b) most significant bits), which determines whether we have a cache miss or a cache hit.

Additionally, the cache contains a Valid bit, which indicates whether a cache line is valid or not (e.g., in order to synchronize data across different caches).

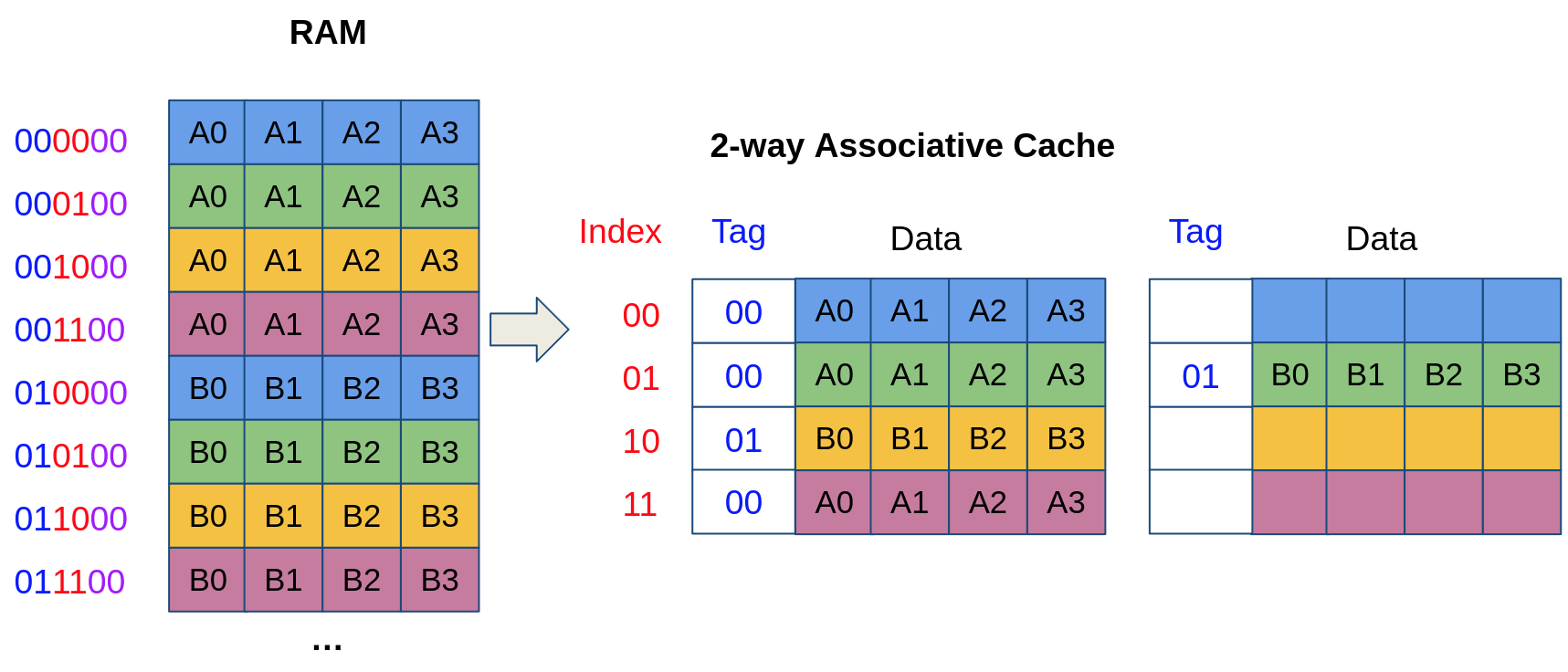

Set-associativity

A limitation of direct-mapped caches is that there is only one block available in a set. Every time a new memory address is referenced that is mapped to the same set, the entire block is replaced, which causes a cache miss. Imagine for instance a program that frequently accesses addresses 000100 and 010100 in the above illustration. Because both addresses map to the same cache set (at index 01), accessing 010100 evicts 000100 from the cache (and vice versa). Hence, accessing both addresses in an alternating fashion results in a sequence of cache misses, which causes a performance loss.

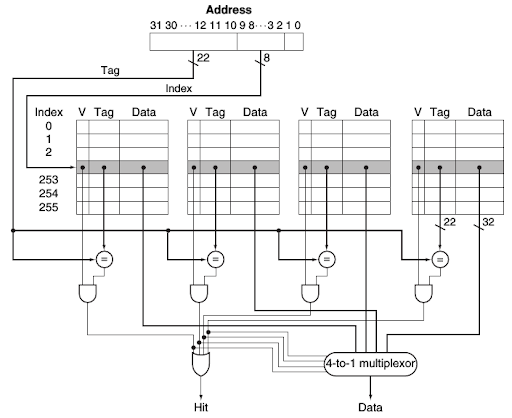

To mitigate this problem, we can duplicate our cache structure into multiple ways, where a given address can be placed into any of the ways. We illustrate below a 2-way cache. Now, even though 000100 and 010100 map to the same cache set (at index 01), they can be placed in two different ways and can be in the cache at the same time!

Finally, a fully associative cache is made up of a single cache set containing multiple ways. Hence, a memory address can occupy any of the ways and is solely identified with its tag (no need for an index because there is only one set!). Fully-associative caches ensure full utilization of the cache: a block is never evicted if the cache is not full. When the cache is full, the evicted line is determined by a replacement policy (e.g., the least recently used block is replaced). However, searching for an address in a fully associative cache is expensive: it takes time (and power) to iterate through all cache blocks and find a matching tag.

Notice that a 1-way associative cache corresponds to a direct-mapped cache. Hence, an n-way set-associative cache provides an interesting tradeoff between a direct-mapped cache and a fully associative cache.

Exercise 1

Suppose a computer’s address size is k bits (using byte addressing), the cache data size (the total of the stored data, excluding the metadata such as tags) is S bytes, the block size is B bytes, and the cache is A-way set-associative. Assume that B is a power of two, so B=2^b. Figure out what the following quantities are in terms of S, B, A, b and k:

- the number of sets in the cache;

- the number of index bits in the address;

- the number of bits needed to implement the cache.

Solution

In this case, we have A number of ways.

Way 1 Way 2 Way A

+---+------------+------------+ +---+------------+------------+ ... +---+------------+------------+

| V | Tag | Data | | V | Tag | Data | ... | V | Tag | Data |

+---+------------+------------+ +---+------------+------------+ ... +---+------------+------------+

| | | .......... | | | | .......... | ... | | | .......... |

+---+------------+------------+ +---+------------+------------+ ... +---+------------+------------+

| | | | | | | | ... | | | |

+---+------------+------------+ +---+------------+------------+ ... +---+------------+------------+

| | | | | | | | ... | | | |

+---+------------+------------+ +---+------------+------------+ ... +---+------------+------------+

Another piece of information we are given is the cache data size, S bytes. This is the total size of all the data blocks, across all ways and sets. This already gives us enough information to calculate the number of sets. The total cache data size is S , this divided by the number of ways, A , gives us the data size of one way ( = S/A ). Dividing this with the block size, B , gives us the number of blocks in one way, which is the number of sets ( = S/(A*B) ).

We are told that the memory is byte-addressable (one memory address corresponds to one byte of data). One such address consists of k bits. In the context of the cache, this address is divided into three parts.

k 0

+-----+-------------+----------------+

| Tag | Set index | Index in block |

+-----+-------------+----------------+

log2(S/(A*B)) b

The least significant bits select the addressed byte from the data block. This data block contains 2^b bytes, which are addressable using exactly b bits (as the number x can be represented using log_2(x) bits).

The next bits select the cache set (referred to as the set index). The same principle applies here. As we know that there are S/(A*B) sets, these can be indexed using log_2(S/(A*B)) bits.

The remainder of the address is used as the tag in the cache. This part of the address makes sure that even if the lower bits of two addresses are equal, the value of one cannot be loaded from the cache when the other one is accessed (because the tag equality check is going to fail). The size of this tag is thus k - log_2(S/(A*B)) - b bits (the total length of the address minus the previous two fields).

We can now calculate the total size of the cache. There are a total number of S/B blocks (total data size / block size). Each block contains 8B data bits and contains the following metadata: 1 valid bit and the tag bits. All together, the cache size is:

= S/B * (8B + 1 + (k - log_2(S/(A*B)) - b))

Exercise 2

Consider a processor with a 32-bit addressing mode and a direct mapped cache, with 8-word block size and a total size of 1024 blocks. Calculate how many bits of the address are used to tag a block, to select the block, a word in the block, a byte in the word. The sum of these numbers must be 32! Calculate the total size needed to implement this cache.

Solution

We see that we have a total number of 1024 blocks. Because this is a direct mapped cache, we also know that the number of blocks equals the number of sets, as there are no additional ways in the cache. From this, we can already conclude that we need log_2(1024) = 10 index blocks to select the set.

We also know that one block contains 8 words. To index one of these words, we need log_2(8) = 3 bits. The 32-bit addressing mode means that one word is 32 bits, 4 bytes long. To select one byte from this word, we need thus log_2(4) = 2 more bits.

This completes the addressing, which means that the remainder of the memory address is used as the tag in the cache. This is 32 - 10 - 3 - 2 = 17 bits.

The total size of the cache is, using a similar calculation as before:

= 1024 * (8 * 32 + 1 + 17)

For each set, we have a block size of 8 * 32 bits, and we have one valid bit and 17 tag bits per line.

Exercise 3

Here is a series of address references given as word addresses: 2, 3, 11, 16, 21, 13, 64, 48, 19, 11, 3, 22, 4, 27, 11. Label each reference in the list as a hit or a miss and show the final content of the cache, assuming:

- direct-mapped cache with 16 1-word blocks that is initially empty;

- direct-mapped cache with 4-word block size and total size of 16 words;

- 2-way set-associative cache, 2-word block size. Total size of 16 words.

The following table shows an example format of a possible solution for a direct-mapped cache with 8 2-word blocks.

+---+----+----+

| S | W0 | W1 |

+---+----+----+

| 0 | 48 | 49 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | 22 | 23 |

| 4 | -- | -- |

| 5 | 26 | 27 |

| 6 | 12 | 13 |

| 7 | -- | -- |

+---+----+----+

2 (miss), 3 (hit) 11, 16, 21, 13, 64, 48, 19 (all misses), 11 (hit), 3, 22, 4, 27, 11 (all misses)

Solution

You can try out all of these exercises in the cache simulator above!

Whenever we have to decide to which set a given address belongs to, it is useful to think about the address’ representation in binary notation. If the block contains multiple words, the least significant bits of the address will determine the word index within the block. The following bits will determine the index of the set. The most significant bits are kept as the tag, which does not play a role in this exercise.

For the direct-mapped cache with 16 1-word blocks, we do not have any word index bits, as one block only contains one word. To index 16 bits, we need the least significant log_2(16) = 4 bits of the address. We might notice that these 4 bits of the address always equal to the result of address % 16 , as the more significant bits represent a part of the address that is a multiple of 16.

Taking 42 = 101010 as an example:

6 4 0

+----+------+

| 10 | 1010 |

+----+------+

The lowest 4 bits (the set index) give the result of 42 % 16 = 10 , while the upper bits (the tag) give the result of integer division: 42 // 16 = 2 . Of course, the sum of these is the original address: 2 * 16 + 10 = 42 .

Using this method, we can place all of the addresses in the first exercise, by using the modulo operation to find the correct set. If a given address maps to a block that is already occupied, we simply replace the contained value (and in practice, we would also replace the tag to know which address the value belongs to).

+----+----+

| S | W |

+----+----+

| 0 | 48 |

| 1 | -- |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 21 |

| 6 | 22 |

| 7 | -- |

| 8 | -- |

| 9 | -- |

| 10 | -- |

| 11 | 11 |

| 12 | -- |

| 13 | 13 |

| 14 | -- |

| 15 | -- |

+----+----+

One hit at the second reference to 11.

If one block contains multiple words, we need to pay attention to two things: first, the lowest bits of the address will be used to index the word within the block, not the set.

In the second exercise, we have a block size of 4 bits, so we use the least significant 2 bits of the address to index these.

As the total size is 16 bits, we only have 4 sets. This means that the next two bits of the address will be used to index these sets.

Taking the example of address 42 again, the last two bits are 10 , so within a block, this address will be assigned to the third (watch out, we start from 0!) word. The next two bits in the address are coincidentally also 10 , so we know that it belongs to set 2.

We can again use a trick: we see that the position of the address in the cache is completely determined by the last 4 bits, so the result of the % 16 operation again enough to place it.

The second thing we need to pay attention to is that when a word within a block is loaded, the neighboring values are also updated (cf. spatial locality). In other words, if address 1 is loaded from memory, the values of the memory locations of 0-3 are all loaded into the block in set 1.

+---+----+----+----+----+

| S | W0 | W1 | W2 | W3 |

+---+----+----+----+----+

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 2 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 3 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

+---+----+----+----+----+

2, 3 (H), 11, 16, 21, 13, 64, 48, 19, 11 (H), 3, 22 (H), 4, 27, 11

If our cache has multiple ways, that does not change the addressing. Within one set, the same addresses can be assigned to any of the blocks in each of the ways. If only some of the ways have valid values stored, a new address will be stored in an unoccupied way. If all of the ways are taken, we usually follow a Least Recently Used (LRU) replacement strategy, which means that we replace the block that has been accessed the longest time ago.

In the third exercise, we have a 2-word block size, so the last bit of the address is used for indexing the word. We know that the cache is 2-way set associative, and has a total size of 16 words. With the block size, this gives us 8 blocks, which are divided into 4 sets, as each set contains two blocks (2-way).

4 sets can be indexed with 2 bits, so in total we use 3 bits of the address for indexing, we can take address % 8 to determine which set and word an address belongs to. The choice of block within the set is down to the replacement strategy we use. Once again, we also need to make sure to only replace full blocks, not just one word in the block.

+---+---+----+----+

| S | B | W0 | W1 |

+---+---+----+----+

| 0 | 0 | 48 | 49 |

| | 1 | 64 | 65 |

| 1 | 2 | 10 | 11 |

| | 3 | 26 | 27 |

| 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| | 5 | 12 | 13 |

| 3 | 6 | 22 | 23 |

| | 7 | -- | -- |

+---+---+----+----+

2, 3 (H), 11, 16, 21, 13, 64, 48, 19, 11 (H), 3, 22, 4, 27, 11

Exercise 4

Associativity usually improves the hit ratio, but not always. Consider a direct mapped cache with 16 1-word blocks and a 2-way set-associative cache with 1-word block size and a total size of 16 words. Find a sequence of memory references for which the associative cache experiences more misses than the direct mapped cache.

Solution

The strength of the 1-word block cache is that it has 16 separate blocks. Although the set-associative has just as many blocks, each block has twice as many potential memory addresses mapped on it. If we use a FIFO replacement, a sequence of 8, 16, 0 would insert and remove 8 out of a set-associative cache. The direct mapped cache would still have the 8.

Additional exercises

Exercise 5

Consider a processor with a 32-bit addressing mode and a 4-way set-associative mapped cache, with 8-word block size and a total size of 2048 blocks. Calculate how many bits of the address are used…

- to select the set

- to tag a block

- to select a word in the block

- to select a byte in the word.